Fat-shaming is something we have all witnessed, if not experienced, at some stage in our lives. From the playground to the boardroom, there are people who say fat-shaming has a positive effect on weight loss.

It involves criticizing and harassing overweight people about their weight and/or eating habits to make them feel ashamed of themselves. The belief is that this may motivate people to eat less, exercise more, and subsequently, lose weight.

However, what is it about fat-shaming exactly which makes people think that this is the best approach? Is it the best approach? What are the potential drawbacks of its use? What does the evidence say?

Having undertaken a Master’s qualification in Weight Management, I have grown accustomed to these questions which is why I will be providing an evidence-based approach to clarify them in this blog.

In today’s post, I’ll be breaking down:

- How fat-shaming is thought to help

- Evidence-based causes of weight gain

- Problem-focused vs Emotion-focused/avoidant coping

- Fat-shaming and weight stigma

- Intrinsic vs. extrinsic motivation

- Evidence of why fat-shaming isn’t effective

- Self-determination theory

- Motivational Interviewing

- Ambivalence

How fat-shaming is thought to help

To begin, the reason why fat-shaming is proposed to help adiposity is based on two beliefs. The first is that those who are overweight or obese are lazy, lacking in self-discipline, selfish, unintelligent or impulsive (Puhl & Heuer, 2009).

I would suggest that it is most likely an assumption based on a combination of all five. Accordingly, it is thought that taking a “tough love” approach, may alter these supposed character flaws of an individual into more favourable characteristics such as motivation, resilience, diligence and dedication to lead to effective weight management outcomes.

Now, by all means, that for some people, these may indeed be reasons why they have gained weight. From personal experience, I know that when I have gained weight in the past, it was mostly due to a lack of self-discipline or a lethargic attitude, last Christmas to give a specific example.

Therefore, to be clear, I am not contesting that these are not legitimate reasons why one may gain weight.

Although, is it just and valid to associate all overweight and obese individuals, compromising one-third of the world’s population now, with these flaws or is it just plain discrimination?

That said, let’s explore the causes of adiposity based on evidence rather than stereotypes.

To read our blog about why we get food comas if food gives us energy, please follow the link here.

Evidence-based causes of weight gain

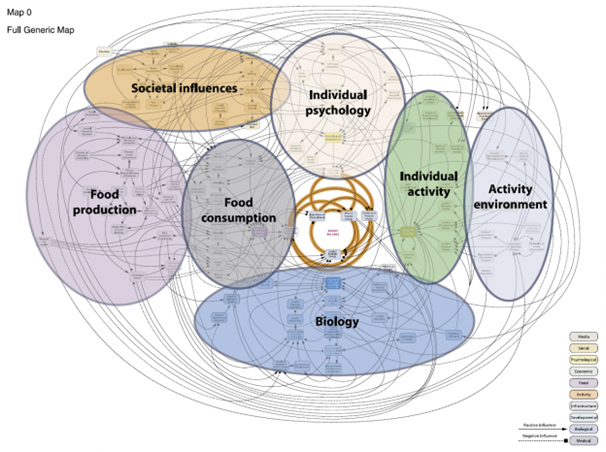

This is the “obesity systems map” from the Foresight report developed in 2007. In it, a team of researchers mapped out the dozens of contributors to weight and the complex interconnections between each.

If you would like to zoom in on each individual causative factor, you can do so here.

This map can be broken down into 7 clusters encompassing:

- The physiology cluster that contains a mix of biological variables e.g. genetic predisposition to obesity, level of satiety and resting metabolic rate.

- The individual activity cluster that consists of variables such as an individual’s or group’s ‘level of recreational, domestic, occupational and transport activity’, parental modeling of activity’ and ‘learned activity patterns’.

- The physical activity environment cluster that includes variables that may facilitate or obstruct physical activity such as ‘cost of physical exercise’, perceived danger in the environment’ and ‘walkability of the living environment’.

- The food consumption cluster that includes many characteristics of the food market in which consumers operate and reflects the health characteristics of food products, such as the level of food abundance and variety, the nutritional quality of food and drink, the energy density of food, and portion size.

- The food production cluster that involves many drivers of the food industry such as ‘pressure for growth and profitability’, ‘market price of food’, ‘cost of ingredients’ and ‘effort to increase the efficiency of production’.

- The individual psychology cluster that contains variables that describe a number of psychological attributes from ‘self-esteem’ and ‘stress’ to ‘demand for indulgence’ and ‘level of food literacy’.

- And finally, the social psychology cluster that captures variables that have influence at the societal level, such as ‘education’, ‘media availability and consumption’ and ‘TV watching.

Therefore, the first underlining belief on which fat-shaming is based, that the concerning population is merely in absence of discipline, self-awareness and motivation, is limited. This belief grossly underestimates the complexity of the condition of which we have just demonstrated.

Problem-focused vs Emotion-focused/avoidant coping

Moreover, the second belief on which fat-shaming is based is that all those who are overweight have a problem-focused coping style.

Let me explain.

Coping has been defined as individuals’ constantly changing cognitive and behavioral efforts to manage specific external and internal demands appraised as taxing or exceeding their resources (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984).

Or, in layman’s terms, coping refers to a person’s conscious effort to try to minimize or tolerate stress and conflict.

Now when we experience stress, in the form of criticism from fat-shaming for example, there are two styles that we may adopt to deal with that stress: Problem-focused coping and emotion-focused/avoidant coping.

Problem-focused coping refers to cognitive and behavioral attempts to deal directly with problems and their effects. Whereas, Emotion-focused/avoidant coping refers to cognitive attempts to avoid actively confronting problems and/or behaviors to indirectly reduce emotional tension

One example to explain the difference would be the coping style someone would use if they start to feel ill.

A problem-focused coping style would be if the person would attempt to get better by going to see a doctor directly. While, on the other hand, an emotion-focused/ avoidant coping style would be if the person stayed in bed and hoped for the sickness to pass. The latter coping responses are often used when individuals decide that the basic circumstances cannot be altered and, thus, they need to accept a situation as it is.

What this means is that those of us who are fortunate enough to employ a problem-focused coping style in response to the stress caused by criticism may indeed take it as fuel to use as motivation in order to lose weight which is, as mentioned, how fat-shaming advocates promote its benefit.

The problem with this idealogy, however, is that the predominant proportion of the overweight and obese populations do not have an active problem-focused coping style. Rather, they have passive emotion-focused/avoidant coping styles as indicated by Varela, Andrés and Saldaña (2019).

The reason why these populations may be more prone to these coping mechanisms is due to the prevalence of discrimination experienced every day by them (Varela, Andrés & Saldaña, 2019).

Everyday.

Fat-Shaming And Weight Stigma

Weight stigma has been documented in educational settings toward obese students by peers, classmates, teachers and school administrators; in healthcare environments, where overweight and obese patients may be vulnerable to bias by healthcare professionals, and in workplace settings, where heavyweight employees are judged negatively by co-workers, supervisors and employers (Schwartz, Chambliss, Brownell, Blair, & Billington, 2007).

Thereby, even when those who are overweight or obese seek assistance from professionals to improve their weight status, they can be met by further discrimination by exactly the same people equipped to assist them.

For example, a study conducted on 107 nurses regarding their attitudes toward obese patients, found that 24% of the nurses interviewed agreed that caring for an obese patient repulsed them alongside 12% reporting that they would rather not touch an obese patient (Puhl & Brownell, 2001).

This is not a dig at nurses, by any means, as this was just a small sample in the study which could have well been within any healthcare profession, it is just to give an example of the severity of discrimination experienced by those with excessive BMIs on a regular basis, which can manifest itself into emotion-focused/ avoidant coping mechanisms.

Blaming themselves, wishful thinking or social withdrawal are common emotion-focused/ avoidant coping styles used by those who are overweight to handle daily problems and stressful situations instead of proactive or problem-solved strategies such as physical activity or seeking social support (Varela, Andrés & Saldaña, 2019).

Further, these passive coping styles are usually accompanied by maladaptive eating behaviours. For instance, they may use food as a coping strategy in response to psychological distress or social conflicts which is called emotional eating (Varela, Andrés & Saldaña, 2019).

So assuming that fat-shaming will intrinsically motivate those with opposing coping styles to criticism than what is anticipated, is incorrect and ineffective.

To read our blog about how to diet for workouts and weight loss, please follow the link here.

Intrinsic vs. extrinsic motivation

However, let me explain why fat-shaming is not even the most effective means for weight loss in those with problem-focused coping styles. To do so, we need to understand the two main types of motivation: Intrinsic and Extrinsic motivation.

Intrinsic motivation comes from, exactly where it sounds like it comes from, within us. While extrinsic motivation arises from outside of us.

Intrinsic motivation is when we engage in an activity solely because we enjoy it and get personal satisfaction from it. Whereas, extrinsic motivation is when we engage in an activity to gain an external reward such as money and respect for example, or to avoid punishment, like fat-shaming.

Indeed, both forms of motivation are effective. Extrinsic motivation is crucial in certain aspects of our lives. For instance, if you’re a taxi driver, you may love driving and getting people to their destinations on time safely (intrinsic motivation). But if you’re not getting paid for it, you can’t put food on the table or provide a good life for your family. We do need extrinsic motivators to keep us focused and committed.

But when it comes to weight loss, it is the intrinsic form of motivation that we want to draw upon more than the extrinsic form such as the cessation of judgment from others.

This is because extrinsic motivation is not sustainable over the long-term which is often the length of time it takes to achieve significant weight loss progress. Fat-shaming may motivate someone extrinsically, but it will only last briefly for a few days/weeks, eventually, that motivation will gradually fade away.

Would the best solution, in that case, be for those striving for a better self to get a fresh batch of fat-shame every several weeks?

I highly doubt it guys.

Even if taking the extrinsic approach does help you to lose your desired weight, once the external motivators have been removed, that motivation will disappear, the initial undesired dietary patterns and a sedentary lifestyle will resurface, and you will end up gaining back the weight that you lost, which, as we are all aware, is extremely common and an issue in its own right.

Although, this is not to say that we are either extrinsically or intrinsically motivated as behavior is complex and people are rarely driven by a single source of motivation. More often, people draw upon multiple forms of motivation when attempting a goal.

For instance, if you are training for a marathon, you may be extrinsically motivated to gain respect from your social circle as well as being intrinsically motivated by the satisfaction you get from the experience of running such as the “runner’s high”. It is better to view intrinsic motivation on one end of a spectrum with extrinsic motivation on the other.

So it is more so a case of shifting from the use of primarily extrinsic to primarily intrinsic motivation.

An example of intrinsic motivation’s effectiveness over extrinsic motivation can be seen from a study on 11,320 West Point military cadets over 14 years by Wrzesniewskia et al. (2014).

What was found was that those who entered West Point because of intrinsic motivation were more likely to graduate, become commissioned officers, receive promotions, and stay in the military compared with those who entered due to extrinsic motivation. Even the participants who had both strong intrinsic motivation (a desire to lead others) and extrinsic motivation (to make more money), did not accomplish as much as those who were solely internally motivated.

Therefore, to answer our original question, why fat-shaming is not the most effective means for weight loss in those with problem-focused coping styles, is because it is an extrinsic form of motivation and better results can be achieved over the long-term from mostly intrinsic motivation.

So now that we have debunked the theories behind how fat-shaming may work and explained why it is not the best form of motivation for change, let’s dive into the evidence of why it doesn’t.

Evidence of why it isn’t effective

One study by Sutin and Terracciano (2013) involving 6157 participants who experienced weight discrimination, found that those who were non-obese had a 2 and a half higher likelihood of becoming obese while those who were obese were found to be 3.2 times more likely to stay obese.

This is in comparison to a study by Jackson, Beeken and Wardle (2014) of 2944 people, which found that weight discrimination was linked to an almost seven-fold increased risk of becoming obese.

Therefore, contrary to the belief that if we criticise those with the use of fat-shaming that they will be motivated to change and solve their weight concerns, the research shows that shame and self-criticism do not inspire adaptive behaviours that enhance weight management outcomes, often quite the opposite in actuality (Gilbert et al., 2014).

To read our blog about fad diets and why we do not recommend them, please follow the link here.

So then if fat-shaming is not the answer, what alternative methods are there to enhance motivation in those struggling with their weight status? How do they utilise intrinsic motivators more than extrinsic motivators in the pursuit of their ideal body weight?

Self-determination theory

And the answer stems from self-determination theory.

Self-determination theory was first developed by two clinical psychologists Edward Deci and Richard Ryan in their 1985 book “Self-determination and intrinsic motivation in human behaviour”.

The theory identifies three psychological needs of a person that are critical in enhancing intrinsic motivation towards a goal: Autonomy, Competence and Relatedness.

The need for autonomy relates to the need to feel volitional in our actions. Competence involves the need to feel capable of achieving desired outcomes (our self-efficacy). And Relatedness reflects the need to feel connected and understood by others (Patrick & Williams, 2012).

And the way these needs can be catered for is through a counselling style called “Motivational Interviewing” from a trained professional. One of the many benefits of motivational interviewing is that it enhances our intrinsic motivation, by way of satisfying these needs, towards goals we wish to achieve.

Motivational interviewing

As people, our motivation consists of a dynamic state of constant behavioral change, which can be swung and influenced by a consultant’s style of counselling (Al, 2017).

The main issue that we see in the weight loss sector today, is the style of communication that most nutritionists/dieticians take with their clients.

This usually involves a directive approach, meaning there is an expectation that once clients are told what to do, they will then follow this advice. However, giving advice alone does not always change behaviour.

Research has demonstrated that this approach can render the client a passive recipient to expert knowledge and can reduce clients’ independence. As a result, it can generate resistance to change (Nice, 2014).

However, on the other hand, if the coach adopts a “goal-directed approach” with a “patient-centered counselling style”, it may enhance the client’s desire to change and decrease resistance (Al, 2017).

Therefore, another reason why Motivational Interviewing is beneficial is because it is a patient-centered counselling style (Al, 2017). It is focused on coaching rather than instructing clients by increasing their levels of engagement and contribution in their treatment or behavioral change (Al, 2017).

So much so, that one study has shown that motivational interviewing provides significant weight loss success at 6 months while enhancing clients’ likelihood of sticking to treatment (Krukowski et al., 2018)!

Ambivalence

The third reason why motivational interviewing is advantageous is that it helps to resolve the ambivalence of weight loss hopefuls. Ambivalence is the state of having mixed feelings or contradictory ideas about something.

Like everyone has about weight loss.

Think about it.

We all know that we need to lose weight for our health, confidence, stress and to feel better, to name a few, but we still don’t exercise as often as we plan to or take dieting as seriously as we opt to.

Mixed feelings.

This is relevant as when it comes to changing our behaviour in order to successfully lose weight, these mixed feelings are often the central barrier and a lack of motivation can actually be a manifestation of this ambivalence (Miller & Rollnick, 1991). Therefore, motivational interviewing allows us to explore this ambivalence and clarify how we really feel about weight loss through the consultation aspect, resulting in enhanced motivation to change.

As Bem (1972) has stated “People learn about their own attitudes and beliefs by hearing themselves talk”.

This is why the consultation component is the main issue within the weight loss sector today. It is the area where the most amount of help may be achieved but is the least utilised.

The therapy relationship accounts for as much treatment outcome as the specific treatment method (Norcross, 2011).

Unfortunately, although nutritionists/Dieticians are highly knowledgeable about providing dietary assessments/advice, they do not employ this counseling approach. The reason being is that the majority are simply not trained in it as of yet.

To read our blog about why you may not be losing as much weight as you may have hoped, please follow the link here.

Conclusion

To conclude, fat-shaming is not an effective solution to inspire weight loss in those who are overweight. The assumptions for its effectivity are made on prejudice rather than fact and all of the current literature on the topic supports the notion that it increases weight gain as opposed to weight loss.

The best strategy to help overweight persons to lose weight is to shift their source of motivation from mostly extrinsic to intrinsic values, resolve their ambivalence towards weight loss and to use a patient-centered counseling style with a goal-orientated approach by an appropriately trained professional.

Fortunately, we here at Plato Weight Management are indeed trained in this key weight loss component and include it in all of our weight management consultations! If you are interested in undertaking our evidence-based and results-backed weight management approach, please make sure to check out our available programs at this link or contact us here!

You can find out what some of our previous clients had to say about the program on our success stories page!

References

Basem Abbas Al, U. (2017). Motivational Interviewing Skills: A tool for Healthy Behavioral Changes. Journal of Family Medicine and Disease Prevention, 3(4), 3:069. https://doi.org/10.23937/2469-5793/1510069

Bennett, G. (1992). Miller, W. R. and Rollnick, S. (1991) Motivational interviewing: Preparing people to change addictive behavior. New York: Guilford Press, 1991. Pp. xvii + 348. £24.95 hardback, £11.50 paper. ISBN 0–89862–566–1. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 2(4), 299–300. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2450020410

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior (Perspectives in Social Psychology). Plenum Press.

Gilbert, J., Stubbs, R. J., Gale, C., Gilbert, P., Dunk, L., & Thomson, L. (2014). A qualitative study of the understanding and use of ‘compassion focused coping strategies’ in people who suffer from serious weight difficulties. Journal of Compassionate Health Care, 1(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40639-014-0009-5

Jackson, S. E., Beeken, R. J., & Wardle, J. (2014). Perceived weight discrimination and changes in weight, waist circumference, and weight status. Obesity, 22(12), 2485–2488. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.20891

Krukowski, R. A., West, D. S., Priest, J., Ashikaga, T., Naud, S., & Harvey, J. R. (2018). The impact of the interventionist–participant relationship on treatment adherence and weight loss. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 9(2), 368–372. https://doi.org/10.1093/tbm/iby007

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, Appraisal, and Coping (1st ed.). Springer Publishing Company.

Patrick, H., & Williams, G. C. (2012). Self-determination theory: its application to health behavior and complementarity with motivational interviewing. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 9(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-9-18

Puhl, R. M., & Heuer, C. A. (2009). The Stigma of Obesity: A Review and Update. Obesity, 17(5), 941–964. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2008.636

Puhl, R. M., Moss-Racusin, C. A., Schwartz, M. B., & Brownell, K. D. (2007). Weight stigmatization and bias reduction: perspectives of overweight and obese adults. Health Education Research, 23(2), 347–358. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cym052

Puhl, R., & Brownell, K. D. (2001). Bias, Discrimination, and Obesity. Obesity Research, 9(12), 788–805. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2001.108

Sutin, A. R., & Terracciano, A. (2013). Perceived Weight Discrimination and Obesity. PLoS ONE, 8(7), e70048. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0070048

Varela, C., Andrés, A., & Saldaña, C. (2019). The behavioral pathway model to overweight and obesity: coping strategies, eating behaviors and body mass index. Eating and Weight Disorders – Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 25(5), 1277–1283. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-019-00760-2

Wrzesniewski, A., Schwartz, B., Cong, X., Kane, M., Omar, A., & Kolditz, T. (2014). Multiple types of motives don’t multiply the motivation of West Point cadets. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(30), 10990–10995. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1405298111